Charles Bukowski’s Lurid Swansong Novel, Pulp. A Review

Review: [Untitled] Reviewed Work: Pulp by Charles Bukowski Review by: William Anthony Nericcio World Literature Today, Vol. 69, №4, Focus on Luisa Valenzuela (Autumn, 1995), pp. 791–792 https://doi.org/10.2307/40151675 • https://www.jstor.org/stable/40151675

Originally published in the great WORLD LITERATURE TODAY → https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org

Republished here so as to include all the pictures the review should have been published with back in the day — written in San Diego, California from 1994 to 1995. c/s Also, and more recently (and as an experiment), published on Medium —> medium.com/@eyegiene/charles-bukowskis-lurid-swansong-novel-pulp-a-review-409f1d081b8a

Charles Bukowski. Pulp. Santa Rosa, Ca. Black Sparrow. 1994. 202 pages. $25 ($13 paper). ISBN 0–876–85926–0.

“It was a hellish hot day and the air conditioner was broken. A fly crawled across the top of my desk. I reached out with the open palm of my hand and sent him out of the game.”

These lines are from the opening page of Pulp, the posthumous “last” novel by our singular American troubadour of the down-and-out, Charles Bukowski, and his words here encapsulate nicely the author’s general concern in this novel with death. With “Lady Death,” to be more specific, and to disclose also the largely allegorical structuring of the piece. With Bukowski’s own recent death, it takes the reader some work to get past see- ing chief protagonist Nick Belane, private dick, as a loosely veiled surrogate for the late Bukowski himself, “a loser, a dick who couldn’t solve anything.”

Bukowski was known for taking self-deprecation to new heights; not for nothing is Pulp dedicated to “bad writing.” Not that he did not respect his works — he did — but he did not take them so seriously that he imagined himself the grand artiste.

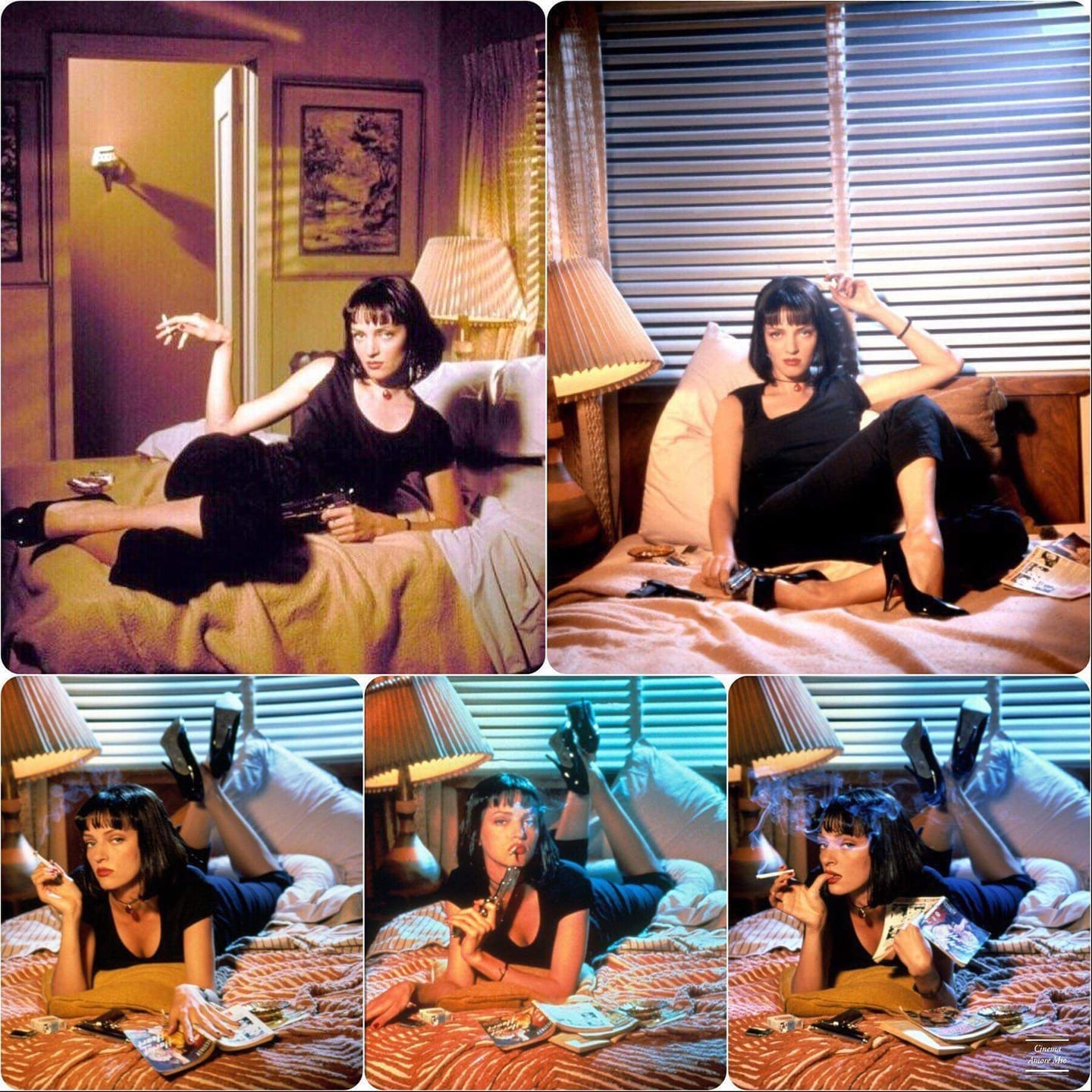

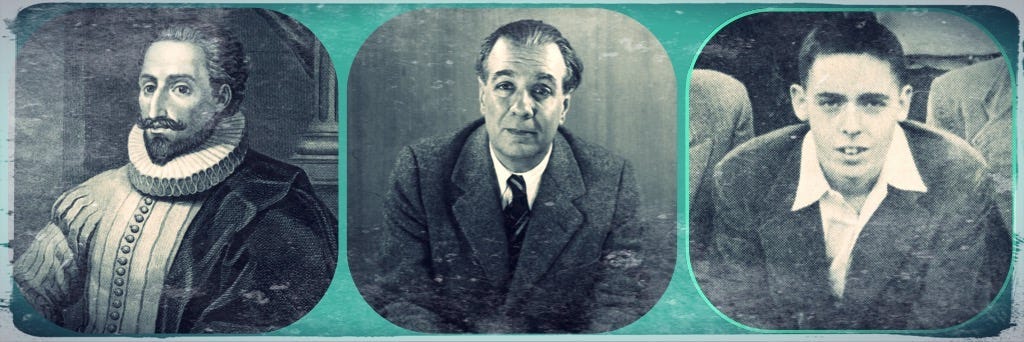

Delusions like that might get in the way of a good drink. Pulp is “pulp fiction” with a twist. As with Quentin Tarantino’s movie Pulp Fiction, the novel Pulp is as much a modest example of the genre’s tawdry domain as a knowing reflection upon its obsessions. In Bukowski’s pages, a grimy, dark potboiler meets an allegory on authoring. Picture, if you will, some chaemeric bastard issue of Mickey Spillane and Laurence Sterne, and you get a sense of Bukowski’s scheme. In the end, our gutter-friendly scribe hands us a “meta-pulp.” This is Hammett and Chandler retooled by a Quixote-era Cervantes, a bowery Borges, or skid-row Pynchon.

Or, shifting medium, Pulp is a painting by René Magritte or Remedios Varo-on black velvet. For example, Bukowski has his private-eye patois down pat. Belane (Spillane?!): “A dick without a gat is like a tomcat with a rubber. Or like a clock without hands.” But there is a manipulative, knowing narratological savvy also in the response by the detective’s antagonist. McKelvey: “Belane you talk goofy.”

Pulp’s plot line merits recording: a shadowy figure called Lady Death hires Nick Belane (“Mr. Slow Death” to his bookie) to find a guy named Celine — yes, that Celine. Ms. Death tells Belane that Celine’s been hanging around Red’s bookstore asking about Faulkner, McCullers [and] Charles Manson.” Bukowski’s Celine is a paranoid boor and gets the novel’s best lines:

on Thomas Mann, “This fellow has a problem he considers boredom an Art”;

on The New Yorker, “One problem there they just don’t know how to write”;

and on writers in general (while fondling a signed copy of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying), “In the old days writers’ lives were more interesting than their writing. Now-a-days neither the lives nor the writing is interesting.”

Wit notwithstanding, Celine meets his maker soon after, again, leaving Belane free to pursue other related cases, which include space-alien bombshells, whores, bars, and red sparrows.

As might be expected, Bukowski’s “pulp” women are worshiped and shat upon by turns. Belane’s threat here to an adulteress named Cindy Bass is typical: “You bitch[] I’ll nail your ass… against the wall.” As the novel muses upon death, salient and somewhat predictable reflections on identity appear, but they are neither winded nor sour with age. Bukowski’s lines are “Sartre” filtered through a pulp vein:

“Was Celine Celine or was he somebody else? Sometimes I felt that I didn’t even know who I was. All right, I’m Nicky Belane. But check this. Somebody could yell out ‘Hey,… Harry Martel!’ and I’d most likely answer, ‘Yeah, what is it?’ I mean, I could be anybody, what does it matter?”

Bukowski accomplishes other feats with this slight novel filled as it is with brief tips of the hat to Bukowski’s lifelong loves: masturbation, “loose” women, bar fights, and booze — lots of booze.

Authors too are duly noted. Celine, mentioned above, comes out well. In addition, two thugs sent to rough up Belane early on are named “Dante” and “Fante” — a salute to Italian maestro Dante Alighieri and Italian-American writer John Fante, writers divided by centuries and region who shared Bukowski’s attentive eye for spiritual darkness.

The novel has its highs and lows: “I checked my desk for the luger. It was there, pretty as a picture. A nude one.”

As you can see, Bukowski is not always subtle. On the whole, however, his staccato prose matches the novel’s spare range, yielding a minimalist homage:

“It was dark in there. The tv was off. The bartender was an oily guy, looked to be 80, all white, white hair, white skin, white lips. Two other guys sat there, chalk white …. No drinks were showing. Everybody was motionless. A white stillness”

With few words, Bukowski charts the singular contours of an eccentric cast with a Samuel Beckett-esque vibe, a Sartrean soundtrack. His neighbor, the mailman, is typical: “His arms hung kind of funny. His mind too.”

Here, readers will find less the labyrinthine literary terrain of C. K. Chesterton and more the moist, fouled corridor of Nathanael West’s fiction.

Rhetorically speaking, I eschew ending reviews with loaded quotations drenched with pathos, but given Bukowski’s recent exit, it seems worth forgoing any expository fastidiousness here. Nick Belane’s reverie is a fitting epitaph to Charles Bukowski the man and his fine last novel:

“All in all, I had pretty much done what I had set out to do in life. I had made some good moves. I wasn’t sleeping in the streets at night. Of course, there were a lot of good people sleeping in the streets. They weren’t fools, they just didn’t fit into the needed machinery of the moment.”

William Nericcio San Diego State University, 94–95.

bnericci@sdsu.edu

malas.sdsu.edu/textmex

instagram.com/william.nericcio